Developing an equitable Mobility-as-a‑Service system: A case study from the Smart Columbus Program

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Posted: 23 June 2022 | Andrew Wolpert - City of Columbus, Diane Newton - HNTB, Sonja Summer - HNTB | No comments yet

Andrew Wolpert, Deputy Program Manager for Smart Columbus at the City of Columbus, in partnership with Diane Newton and Sonja Summer from HNTB, provides Intelligent Transport with in-depth insight into the Smart Columbus Program, which highlighted the possibilities for MaaS when digital and physical infrastructure collide, ultimately supporting the outcomes of both mobility and opportunity.

In December 2015, the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) launched the Smart City Challenge (SCC), asking mid-sized cities across America to develop ideas for an integrated, first-of-its-kind smart transportation system that uses technology to help people and goods move more quickly, cheaply and efficiently. Columbus won the SCC in 2016, after competing against 77 cities, which included a $40 million award from USDOT.

The Smart Columbus Program aimed to improve quality of life; drive growth in the economy; provide better access to jobs and ladders of opportunity; become a world-class logistics leader; and foster sustainability”

The Smart Columbus Program aimed to improve quality of life; drive growth in the economy; provide better access to jobs and ladders of opportunity; become a world-class logistics leader; and foster sustainability. The city demonstrated how advanced technologies can be integrated into other operational areas within the city, using advancements in Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS), connected vehicles (CVs), automated vehicles (AVs) and electric vehicles (EVs), while integrating data from various sectors and sources to power these technologies and leveraging the new information that they provide.

The Smart Columbus Program deployed a holistic portfolio of eight projects and six outcomes. Three of these projects highlighted the possibilities for Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) when digital and physical infrastructure collide, supporting the outcomes of mobility and opportunity. This article highlights how the city evaluated MaaS from both a multimodal and automotive/driver perspective; the innovations that were achieved by creating holistic relationships among these projects to maximise community impact and achievement of MaaS; and the challenges and opportunities that remain for other deployers.

Existing transportation system

The Columbus area is characterised by high Single Occupancy Vehicle (SOV) usage, low transit usage and low-density urbanisation. Key consequences of these characteristics include car dependency, a pre-existing lack of trust or familiarity with multimodal travel options and a perception of excessive trip time and service uncertainty with respect to existing transit services.

Some of these challenges and perceptions were centralised in specific areas of the city. For example, residents of the Linden neighbourhood face numerous socio-economic challenges, including low household income, lack of major employers and high infant mortality rates. These problems are compounded by the lack of access to transportation options, as there are numerous job centres throughout the Columbus region, including some that are a short drive from this neighbourhood. In addition, although community resources are located near the neighbourhood, they are somewhat disconnected from the neighbourhoods themselves and the transit centres that serve them: close, but not close enough. This results in a transit gap for visitors and patrons of St. Stephen’s Community House, which provides a wide range of community services, including a food pantry, as there is no direct transit access to the site from existing bus routes.

Finally, there is also an inherent distrust in emerging technologies. To simultaneously overcome this distrust while also solving these very real challenges (especially related to a lack of first-/last-mile (FMLM) transit options), Columbus sought to demonstrate automated vehicle technology in a manner that would fit within the transit ecosystem, specifically addressing access to community services from existing transit routes.

The solution: Mobility-as-a-Service

The International Transport Forum (ITF) recently published ‘The Innovative Mobility Landscape: The Case of Mobility as a Service’ to evaluate the delivery models of transportation in urban and non-urban environments1. In its report, ITF states: “Mobility is essential to improve human welfare, especially in urban and peri-urban areas where the majority of the world’s population is concentrated… A one-size-fits-all approach to addressing the benefits and challenges of urban mobility cannot work. Mobility needs vary by geography and population; global regions display significant differences in terms of urban transport mode shares and travel behaviour.”

MaaS can serve as a solution that provides significant benefits by developing a holistic transportation ecosystem that includes public and private mobility providers and reliable and equitable access to transportation”

MaaS can serve as a solution that provides significant benefits by developing a holistic transportation ecosystem that includes public and private mobility providers and reliable and equitable access to transportation. ITF defines MaaS as “a distribution model for mobility, not as a mobile app or a travel mode. MaaS is a model for supplying passenger transport services through a digital customer interface that allows users to source services from a variety of operators, either privately or publicly operated. At its core, MaaS seeks to provide a smooth and reliable customer experience. MaaS involves identifying clients and operators, gathering information about the availability of services and capacity, and managing payment and revenue allocation within a common digital framework. It requires the production of mobility services by public and private sectors, joining these into an integrated offer and a means to communicate this offer to potential travellers.”

With this background in mind, Columbus defined MaaS as a shift away from personally-owned vehicles to a solution that combines both public and private transportation services and delivers them both physically and digitally. The city became a facilitator for MaaS by holistically integrating three of the portfolio projects, providing trip planning, access and new mode choices to users across Columbus, but especially in the opportunity neighbourhood of Linden. These projects included:

- The digital solution: the Multimodal Trip Planning Application (MMTPA), which provided a mobile app, branded as Pivot, which integrates end-to-end trip planning, booking and seamless payment across all modes of transportation, whether public or private

- The intersection of physical and digital: Smart Mobility Hubs (SMH) meet human needs through the application of technology that focuses on prevention as well as remediation of problems and maintains a commitment to improving the overall quality of life of users

- The physical solution: Connected Electric Autonomous Vehicles (CEAV) were piloted to increase access to public transportation, jobs and services. Although an emerging technology project, the shuttles operated in a mixed-traffic environment, interacting with other vehicles, cyclists and pedestrians. There were two demonstrations conducted during the project, one downtown and one in the Linden community, with two of its stops overlapping with SMH locations. The CEAV service was also one of the modes featured in Pivot.

Together, these projects worked in harmony to provide safe, reliable and equitable transportation to all residents. This paper summarises how each project is solving a mobility problem using both physical and digital infrastructure; the challenges and lessons learned during deployment; and how the projects were intertwined to create a MaaS environment.

The Smart Columbus MaaS concept

The desired outcome was to improve mobility in Columbus communities and to improve opportunity by increasing access to jobs and job centres in the region for communities in need of travel options”

It was the city’s goal that the holistic suite of mobility-focused projects would allow residents to access the transportation systems available in Columbus today and in the future more easily, so that they can maximise services to improve their lifestyle. Together, the MMTPA, SMH and CEAV projects provided an innovative solution to improve mobility and access to opportunity. Columbus identified the following objectives to evaluate the measurable impact of these projects:

- Facilitate improved access to multimodal trip planning information

- Increase usage of the available transportation services Improve ease of multimodal trip planning

- Provide travellers with more convenient access to transportation service options

- Increase access to jobs and services

- Increase customer satisfaction.

The desired outcome was to improve mobility in Columbus communities and to improve opportunity by increasing access to jobs and job centres in the region for communities in need of travel options.

Digital solutions: MMTPA

The MMTPA project was designed to allow travellers throughout Columbus and outlying communities to create multimodal trips and pay for services using a single, account-based system linked to different payment media and modes of transportation. The vision for Pivot was to provide a platform that integrates end-to-end trip planning, booking, electronic ticketing and payment services across all modes of transportation, whether public or private.

The vision for Pivot was to provide a platform that integrates end-to-end trip planning, booking, electronic ticketing and payment services across all modes of transportation, whether public or private”

The multimodal trip options included in the app are walking; public transit (operated by the Central Ohio Transit Authority (COTA)); the Ohio State University Campus Area Bus Service (CABS); ride-sharing (Gohio Commute); bike-sharing (CoGo); scooters (Bird, Lime, Link); ride-hailing (Yellow Cab, Uber, Lyft); as well as personal bikes and vehicles.

Pivot offers real-time mobility options for users in the Columbus region. Users are able to see nearby ride options for buses, scooters and bikes, and receive live transit alerts through the app. Pivot’s many features include a sophisticated navigation system with turn-by-turn instructions, and is available on multiple platforms including Android, iOS, Smart Mobility Hub kiosks and online. Pivot was built on the following design principles:

- A foundation of open-source and proven technologies, with no dependencies on subscription services, proprietary code or commercially licensed data

- Flexible hosting options due to the containerised open approach to development

- A distributed ledger (‘blockchain’) which offers redundancy, transparency, shared governance and long-term viability

- Users book trips with the assurance that their travel history and other personal information is not available to anyone, including the project team, unless they volunteer to release certain information for platform improvement or trip booking

- Machine learning for optimised trip planning results.

Through data from mobility providers, Pivot can connect travellers to a physical mode using a digital travel solution (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Pivot methodology.

The intersection of digital and physical solutions

The desired outcome was to improve mobility in Columbus communities and to improve access to jobs and job centres in the region for communities in need of travel options. The Pivot app, website and SMH kiosk app all run the same codebase, while properly tailored for the look and feel of each device type. SMH includes a free-standing kiosk that provides a user interface with Pivot. Travellers can plan and execute trips by sending trip plans from the kiosk to their smartphones to open in Pivot (Figure 2). Additionally, the CEAV route was incorporated into Pivot as a mobility service option.

Figure 2: Smart Mobility Hub kiosk with Pivot displayed.

Physical solutions: Smart Mobility Hubs

If the MMTPA was the digital solution to creating MaaS, the SMH project was the physical embodiment of the concept. These hubs were designed to improve the availability of transportation options for people living in areas with limited connectivity, leveraging COTA’s Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) route. Six SMHs were deployed to provide travellers with consolidated mobility options and transportation amenities, such as Interactive Kiosks (IKs) with Wi-Fi and Emergency Call Buttons (ECBs), enabling modal transfers between a variety of transportation options that exist, and providing access to comprehensive trip-planning tools – especially Pivot. Taken together, these services were intended to facilitate MaaS.

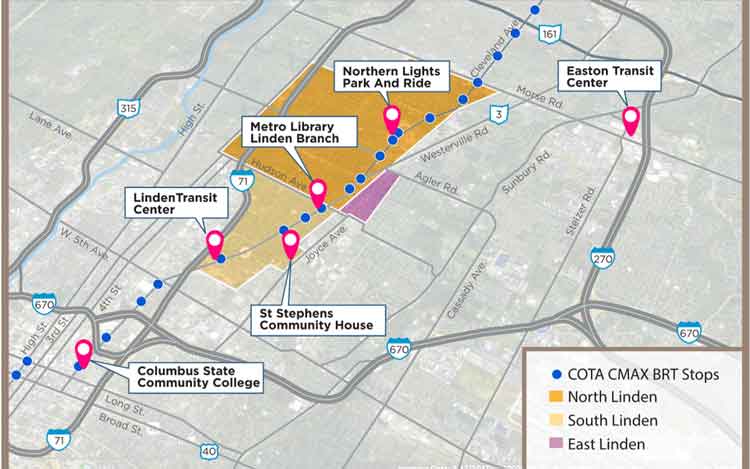

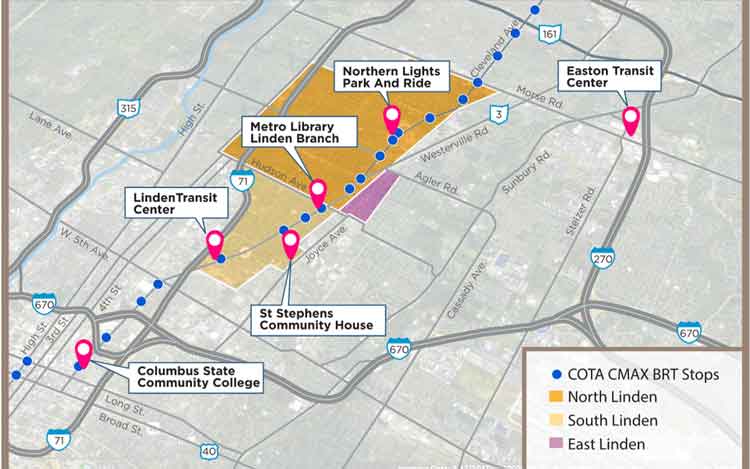

Through several workshops in the Linden Community, the project team determined that there were six preferred Smart Mobility Hub locations based on the input received and where the community saw FMLM gaps (Figure 3). To identify the mobility services to be provided at each site, the project team then transitioned to co-ordinating with the site stakeholders to deploy what was preferred by the property owners, and what fit within existing geometric constraints. This co-ordination concluded with not every SMH containing the same amenities – however, each hub provided a MaaS system both physically and digitally. Continual stakeholder engagement was critical in transforming the high‑level vision of SMHs into a product that would meet the real needs of the community.

Figure 3: Smart Mobility Hub locations.

Working with SMH site stakeholders was key to the success of the SMH. Each of the site stakeholders was responsible for the ownership and maintenance of their sites, and any improvements or access that the project was granted had to have minimal impact to the business operation of the site. Input and agreement were also required to finalise the physical design of the SMH, particularly where parking facilities, drop-off lanes or other space-intensive uses needed to be dedicated to particular mobility services.

Even in the instance of Columbus State Community College, where no improvements were on private property, the co-ordination between the project team and the stakeholder allowed the SMH to be installed in a fashion that did not impact the campus master plan and future improvements to the adjacent property. The site stakeholders also provided critical input on the modes available at each site. There were geometric constraints that prohibited some improvements, such as a Park and Ride where few parking spaces were available, or other considerations such as traditional bike racks leading to site clutter or other challenges.

Innovative physical solutions: Connected Electric Autonomous Vehicles (CEAV)

The CEAV was integrated with the Pivot app so that users could include the CEAV in trip planning to make the connection to COTA. The Linden LEAP provided a FMLM connection in the Linden neighbourhood seven days a week from 06:00 to 20:00. The route had a total of four stations, connecting two SMHs at each end of the route. The route selected was identified through stakeholder input as a solution to a transit gap for visitors and patrons of St. Stephen’s Community House, which provides a wide range of community services, as there is no direct transit access to the site from existing bus routes.

Passenger service launched on 4 February 2020 and operated until 20 February 2020, when an emergency stop resulted in a passenger slipping from her seat. Passenger service was suspended, and the shuttles continued to operate testing and training runs with only project staff onboard to evaluate all potential reasons and factors for the sudden stop.

On 4 April 2020, all operations ceased due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) approved proposed safety mitigations for the vehicle vendor, EasyMile, to return to passenger service in May 2020, the persistent global pandemic impacted the ability to implement mitigations following the incident, and also led to new challenges related to passenger service, with the importance of social distancing and increased sanitising procedures.

As the City of Columbus consulted with its stakeholders to determine how the shuttles could otherwise be used to serve the immediate needs of the community, it was recognised that there was alocalised and increasing need in the community to connect residents to food and support services”

Therefore, the Linden LEAP food pantry service was launched on 30 July 2020 due to several pandemic-related factors. First, state and local guidelines stressed the importance of ‘social distancing’, defined as maintaining six feet of separation from another person, and increasing the necessary sanitising procedures, which greatly limited the ability of the EasyMile EZ10 shuttles to accommodate passengers. Second, as the City of Columbus consulted with its stakeholders to determine how the shuttles could otherwise be used to serve the immediate needs of the community, it was recognised that there was alocalised and increasing need in the community to connect residents to food and support services.

When the pandemic-related directives went into effect, the on-site food pantry at St. Stephen’s Community House shifted from a choice food pantry, where patrons would choose food from shelves to take home, to a pre-packaged system. St. Stephen’s also saw a significant increase in demand during this time. Therefore, it was proposed that the Linden LEAP transform its mission to a food pantry box delivery service that picked up boxes from St. Stephen’s and travelled to Rosewind, the largest public housing development in Columbus. By using the food pantry delivery service, the shuttles would be able to serve many households throughout the pandemic to help to alleviate food insecurity.

Operations

Pivot was first made available to the public in September 2019, with the official marketing launch in December 2020. Data from Pivot was reported as trip segments, or how many legs there were in a single trip. For example, a trip could include multiple modes, such as a personal vehicle, to bus, to scooter. Each mode used is considered a trip segment. Prior to the public launch, there were 2,354 trip segments using Release 3 of Pivot. Following the public launch, there were 1,000 trip segments during the evaluation period.

Over eight per cent of the food pantry service’s patrons walked to the shuttle and did not drive, so bringing the food into the community eased the two-mile walk to and from the food pantry”

The food pantry service for CEAV operated from 12:00 to 15:00, Monday through Friday. The service delivered 3,598 boxes and 1,526 masks into the community from 30 July 2020 through to 1 April 2021. Over eight per cent of the food pantry service’s patrons walked to the shuttle and did not drive, so bringing the food into the community eased the two-mile walk to and from the food pantry with a 30- to 40-pound box. With each box containing three meals per day for four people, and three days’ worth of food, the Linden LEAP pantry service distributed 129,528 meals into the community during its eight months of food delivery.

Recommendations and lessons learned

For cities and agencies considering the development of a MaaS system, there are several items to consider during planning, design and deployment. As Columbus developed its MaaS system with the deployment of Pivot, SMH and CEAVs for FMLM connections, the city learned many lessons along the way.

Conclusions

MaaS can serve as a solution that provides significant benefits by developing a holistic transportation ecosystem that includes public and private mobility providers and reliable and equitable access to transportation. There are many types of programmes and projects that can work together to achieve MaaS. Columbus’ vision may vary from other cities and agencies, however, a fundamental tenet must be the ability to provide accessible and equitable transportation for all.

A MaaS platform is achievable – the Pivot app integrates the services of multiple mobility providers to facilitate multimodal trip planning and trip execution through a single interface with links to third-party apps for payment. To achieve MaaS, transit agencies should continue to serve in a key role. Cities often have regulatory/permitting mechanisms for providers, but public transit can build relationships to encourage connection to transit and the building of a MaaS system. All entities need to work together for it to be successful.

Public transit can build relationships to encourage connection to transit and the building of a MaaS system. All entities need to work together for it to be successful”

The SMHs are a support service to enable MaaS deployment and, as travel returns to the region after the pandemic, it is anticipated that mobility hub use will increase. Columbus will support growth and further deployment of SMHs across the city to enable transit-dependent residents to better access basic services, such as health care, grocery stores and banking.

The CEAV project addressed the challenges presented in the city’s SCC vision in using urban automation to solve FMLM challenges through the Linden LEAP passenger and food pantry services. The challenges indicate that the time for full autonomy is still in the future, as the technology and sensors are not ready for every‑day, every-situation Level 5 automation. The path to autonomy is dependent upon demonstrations such as the CEAV project, which has provided valuable data, institutional learning and resident awareness that can assist the development and acceleration of the technological advancements. By creating a community-based environment for the deployments, the project team was able to foster ownership and pride in the effort.

Through these three Smart Columbus projects, the city was able to provide mobility and opportunity to the Linden neighbourhood. The coming together of these projects allowed the residents easier access to COTA’s fixed route bus line, connecting them to their desired destination whether it be employment, education or health.

Reference

1. ITF. The Innovative Mobility Landscape: The Case of Mobility as a Service. International Transport Forum Policy Papers, No. 92, OECD Publishing, Paris. 2021.

Related topics

COVID-19, Multimodality, Passenger Experience, Public Transport, Sustainable Urban Transport

Issue

Issue 1 2022

Related modes

Bus & Coach

Related cities

Columbus

Related countries

United States

Related organisations

HNTB, Smart Columbus, The City of Columbus

Related people

Andrew Wolpert, Diane Newton, Sonja Summer