Ensuring sustainability is at the heart of the future of mobility

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Posted: 17 September 2019 | Maya Ben Dror | No comments yet

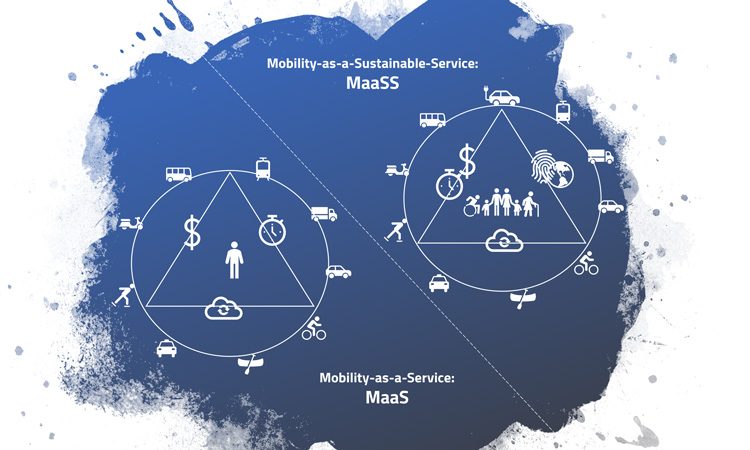

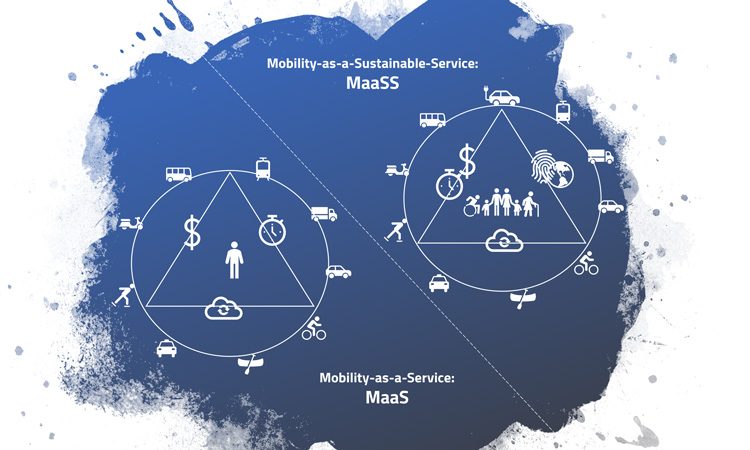

As we shift to Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) and focus on a seamless travel experience, we shouldn’t assume sustainable services will come naturally, warns Maya Ben Dror, Lead of the Future of Mobility at the World Economic Forum. Mobility-as-a-Sustainable-Service (MaaSS) is the key to bringing greener commutes, not just interconnected ones, to the centre of our cities.

As our mobility options change, so will our relationship with them. Today, mobility is no longer a permanent asset we must own, such as a car or bike, but instead a fluid service we can tap into only when we need it.

There is no one term capable of capturing the disruption we face in urban communities across geographies and cultures, because the disruption is multi-faced and very local: you may be using your mobile device to book a ride, share a ride, order goods to your doorstep, hire a bike for a short journey, pay for a transit service or be frustrated by scooters on roads and pavements.

What is probably true for all of us, however, is that this disruption was the catalyst for us to re-think mobility; the time and money we spend on it, how it is distributed on our city streets, and who or what should have the ‘right of way’.

What most now comprehend is that mobility is no longer an asset we need to own (a car or bike for instance), or an unpredictable transit option we depend on, but rather a flexible need-specific service we can use and pay for only as we need it. We can now get to places that will put us on a path to reach our destinations, be it career, family or self-development related, without spending money up front and devoting extra time to maintaining and parking mobility products we only really use about five per cent of the time. MaaS and mobility on demand (MOD) are perhaps the most used terms aimed at explaining this disruption. MaaS is often used in Europe to describe a seamless user mobility experience across modes, while MOD is the term often used across the other side of the Atlantic to manifest various demands for mobility, from commute to goods delivery.

While aligning on what we mean when we design MaaS or MOD is very important, especially among policy makers and different private sector actors, the user perspective is very much like everything else in the digital era – it is about a seamless experience. Such experience is often described as a one-stop-shop. Payments over one platform (for example, Whim, Ubigo) is the focus, and not surprisingly, the public-private-people battle over who owns what data quickly follows. I argue that by re-focusing the conversation on Mobility as a Sustainable Service (MaaSS) we may be able to leapfrog the current multi-mobility providers’ data sharing hurdle.

Over the past six months the Forum’s Future Mobility Platform convened practitioners, academics and companies in the U.S., Europe and China to garner diverse insights on how to make the transition to sustainable mobility service a simple process. We agreed that we need to ensure not only a safe and convenient experience, without which MaaS will not be feasible, but also a sustainable new mobility system. If emissions keep rising, damaging our health and brain development and warming the planet to a degree that urban heat waves become an unbearable habit, our lives will not be better. If we do not seize the opportunity to transition to a mobility system in which everyone has access to work, service and leisure, our economies will weaken and society will become even more divided.

Credit: World Economic Forum

The group curated by the Forum built its work on a cumulative number of studies showing that by combining shared, electric and automated mobility (SEAM), emissions could be reduced by 80-90 per cent and even faster than if we were to let technology and economy take their course without deliberate guidance. Moreover, our mobility spending would decrease by 40 per cent, or in other words, we would have more cash-flow to invest in our desires and aspirations while we overall spend less money and time on, quite literally, getting there. The multi-stakeholder group therefore drafted a four-step governance framework prototype and is offering its support to cities as they struggle to put today’s linear policy making on track to a dynamic MaaSS future. By creating a template that cities can adjust to their own contexts, the time to achieving MaaSS is shortened. By offering the support of (often competing) mobility service providers (MSPs), mobility incumbents and experts, innovative policies can be developed.

By refocusing on a MaaSS discourse, we can align and agree on a mobility future that business and cities can thrive in. Stakeholders can be motivated to work collaboratively for achieving such a future.

Four key issues are to be accounted for when pursuing MaaSS:

MaaSS is a process-focused effort

Cities around the globe seek to define their emerging mobility principles and alliances are emerging to guide this trend (NUMO’s, to name a prominent one). Such principles can serve as lighthouses for policy making. However, it takes more than just a set of principles to work the magic. In complex system theory, tested in nearly every field of research – from health to space, dynamic policy is increasingly seen as a science that evolves through discourse. Perhaps intuitive to those engaged with polities, meanings, beliefs and social phenomenon are found to influence policy more than knowledge. Therefore, policy design needs to shift from goals to a processes-focused discourse in which inclusiveness and communication are two very powerful tools. One of the first areas in which this was truly demonstrated is sustainable policy, such as climate policies. Inclusiveness in mobility means not only hearing everyone out, but also translating knowledge into action by making sure new mobility systems can truly serve everyone in our city. Every city would need to co-design a multimodal mobility system with, and for, its unique communities.

MaaSS for all: your past, present and future self

Different people have different mobility needs, and this goes beyond efforts to make mobility accessible to people with physical and mental disabilities. Many studies investigate the inability of new mobility services to reach populations in ‘mobility deserts’, often also at the margins of socio-economy (yet another chicken-and-egg problem). A basic economic formula will tell that places with less demand or abrupt demand will see less supply. Japan is focusing on this problem, as well as other areas in the world where ageing populations have next to no mobility options for going about their basic daily needs. However, people also have varying needs throughout their life. Many of us have, or will, spend our 30s and 40s driving a car because we need to care for our children. Companies like Zum and Kango are trying to free children’s caregivers from the “got to drop the kids off” mobility pattern that makes a car so central to young families. When we design for MaaSS, we should not leave our parent-self or our elderly-self behind: we should not only design for different physical and mental needs, but also to care for those that need it.

MaaSS leaps 20th century taxonomy

Multimodality is key to a sustainable and inclusive mobility system. Yet we still use operator-dependent taxonomy (public transit, private cars) as if the emerging integrations between private and public players, on-demand shuttles enabled by Via, for example, aren’t the way forward. We also still break down mobility products to markable segments (SUV, luxury), as if we care what car we ride even when we don’t own it and our socio-economic identity is no longer associated with it. If we are to advance MaaSS, we should remove 20th century ownership-associated wording and make way for definitions more closely related to what we expect of new mobility services: by zones and by time of operation (rush-hour shuttle), by occupancy (capacity to carry passengers and goods), by energy type (are you up for an uphill bike?), or by environmental footprint (wait a couple more minutes to ride a zero-emission mode). MaaSS choices of commute can already reward those that use them, through apps like Miles.

Co-design dynamic MaaSS-attuned policies

Cities around the world use road zipper to create dynamic road widths – two lanes during off-peak times and three lanes during peak times. Cities are now also more willing to set congestion pricing – another less popular dynamic tool to fight congestion. However, whether they will be able to harness this to generate a more sustainable system by differentiating fees for zero-emission and shared rides remains unclear. It is also not obvious whether dynamic design of charging infrastructure, parking, loading hubs and other creative ways to incentivise MaaSS will be developed in tandem with MaaS payment platforms.

It may very well be that the incentive to first-mile on-demand mobility put in place to help people out of their single occupancy modes and into high occupancy modes in the morning, are not serving the same people in the evening in the same way. And different neighbourhoods may have very different needs as well. Our simplistic assumptions of mobility should be challenged, especially as work-life harmony takes centre stage and flexible lifestyles are adopted by more workplaces that nudge commuters in and out of business centres.

Mobility is a shared entity, one that encapsulates the public, private and the people. As cities are projected to grow by 30 per cent over the coming decade, the opportunity to bring people back to the centre of our cities in a sustainable manner is here now, and the pathway is MaaSS, not just MaaS.

Related topics

Mobility Services, Multimodality, Sustainable Urban Transport

Related organisations

World Economic Forum