Mission “Begin Again” and Mumbai’s mobility woes

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Posted: 20 November 2020 | Shristi Gupta - Central Railway, Vignesh. P - The Bridge Project | No comments yet

With the highest congestion rates in India and problems with pollution, Mumbai needs to seriously rethink its transport network. That’s according to Shristi Gupta and Vignesh P, who discuss what India’s most populous city needs to change.

Mumbai is the most congested city in India with more cars per kilometre of road than anywhere else in the country.

Mobility is the lifeblood of civilisations, as it spurs economic activity and shapes societies. Cities depend on robust transportation systems for their growth and sustenance. Mumbai – India’s famed Urbs Prima – is no different. The city’s transport scenario, however, has been riddled with problems and paradoxes. Gradual resumption of economic activity in the city has also been accompanied by demands to normalise Mumbai’s public transport services. This phase, aptly titled “Mission Begin Again”, has witnessed harrowing narratives of people commuting for over 8 hours in a day.

For the safety of commuters, the Central Road Research Institute (CRRI) has issued guidelines on the effective social distancing measures and strategies to be followed in all modes of transport. The challenges of adapting to such measures has once again brought to fore the city’s inflexible transportation woes. Exploring this further, we look at the underlying paradoxes in Mumbai’s transport landscape and the possible way forward.

The frontrunner in public transport and congestion

Mumbai has traditionally had a higher public transport (PT) modal share (59 per cent as per CMP) as compared to most other cities across the globe. Concurrently, it also reported the world’s highest congestion in 2017, 2018, 2019 and was the fourth highest in 2020. The vehicle density in the city is alarming, with an average 1900 vehicles packed in just 1 km of road length.

In terms of car congestion, Mumbai is way out in front with 530 cars per km. The next highest in India is Delhi with around 109 per km – five times less than Mumbai, despite having more cars than Mumbai. A striking factor is the road length between the two cities. While Mumbai has just about 2000 km of road length, Delhi has about 17,000 km road length – eight times more than Mumbai.

The traffic situation is further exacerbated by ongoing construction works for other infrastructure developments. Average speeds were just 18kph and at arterial places this drops down to 10kph during peak hours. Post the COVID-19 induced lockdown, in spite of lower total overall volume, the congestion is slowly coming back. Drivers spent an additional 24 per cent time in traffic compared to 17 per cent by the end of July 2020. Effectively, Mumbai’s commuters have no respite from severe congestion despite the high patronage of public transport or even during COVID-19 induced lockdowns.

With public transport not fully operational as of October 2020, there has been renewed interest in car sales in August and September with a robust growth of 35 per cent year on year. Going by this trend, it is estimated that Mumbai’s roads will have almost 4 million vehicles by the end of this financial year. This could put further strain on an already perilous infrastructure, increasing congestion on roads and exacerbating pollution.

The World Bank, in its report on traffic congestion in India, draws attention to ‘uncongested mobility’ as the aspect of congestion caused on roads due to obstruction of carriageways by non-vehicles such as pedestrians, cattle etc. This is one of the major reasons for congestion in India.

The congestion pattern in India is also at odds with other parts of the world, as there isn’t a definite peak and off-peak rush hour pattern, instead traffic spikes throughout the day and wanes towards nightfall. Therefore, congestion is an enduring phenomenon in Mumbai, not being restricted to any hour.

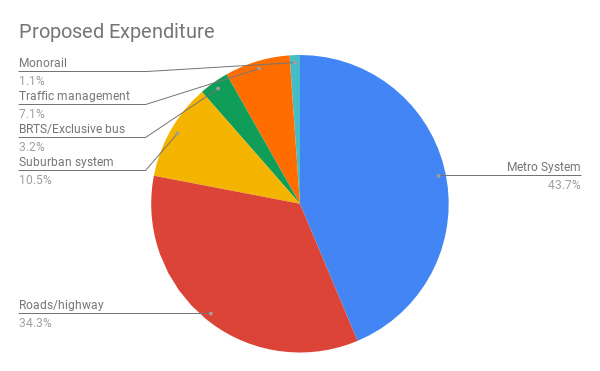

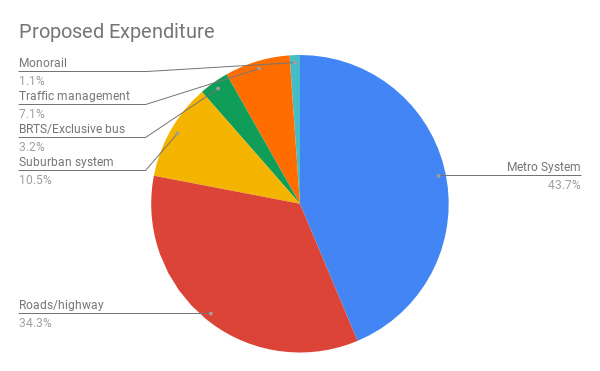

It also pointed out that measures such as congestion pricing attempted in other parts of the world may be of little use. Instead, investments on public infrastructure are more critical. However, as is reflected in the share of proposed expenditure on various kinds of transport networks in the Comprehensive Mobility Plan-2034 (CMP), transport planning in Mumbai has abetted the growth of private vehicle based transport which already occupy over 75 per cent of the city’s road space.

Chart 1: proposed expenditure on various modes as per Comprehensive Mobility Plan -2034

While it did help that the majority of MUTP’s funds were targeted to capacity augmentation of the city’s suburban rail network, an inability to undertake holistic modernisation of suburban rail made it extremely ill equipped to handle a crisis like this one. For instance, local train stations lack key systems like access control at entrances, passenger counting mechanisms and self-closing doors in trains, making the task of crowd control impossible. Similarly, ticketing in both railways and public buses is largely manual, making it difficult to control ticketing using technology as is happening in many countries across the world. COVID-19 has reinforced the importance of public transport in a city like Mumbai and serves as a stark reminder of the high opportunity cost of diverting funds away from public transport.

The Invisible Last Mile

As per CMP, it is estimated that 60 per cent of trips on public transport start or end with walking. Maharashtra state government’s draft transport policy calls for 80 per cent trips to be made through walking, cycling or public transport. If the aim of increased public transport usage is to be met, then proper planning and integration of the last mile commutes from all the systems is intrinsic. Last mile journeys, however, remain largely invisible in planning and require greater policy attention.

In a survey carried out just before the onset of COVID-19 by the authors, over 70 per cent of respondents indicated that they used taxis or private vehicles to reach home from the suburban stations.

Promoting the infrastructure for safe and environment friendly modes of last mile journeys at stations may be a good starting point, with transformative spin offs for the overall transport scenario in the city. For instance, around some stations, it would be prudent to introduce and invest in electric bike sharing as a last mile option and in others, investing on walking pathways with proper street lights would be more effective. There can be no ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to this.

In these challenging times, cities the world over provided an impetus to cycling and walking as prominent modes of transport. For instance, Paris is rolling out 650 kilometres of cycleways, including a number of pop-up “corona cycleways”. In China, during February and March,2020, the number of cycle trips longer than three kilometres was double that of the same period last year. These helped commuters to get on with their daily lives despite major disruption to the transport system.

Mumbai appeared ill-equipped on this aspect too. According to a newspaper report of October 2020 Mumbai had about 2.3 million two wheelers occupying 28 per cent of the city’s road space. However, had Mumbai been equipped with adequate cycling infrastructure, short distance trips could have been undertaken using bicycles, leading to lower pollution and congestion.

As per CMP, 46 per cent of trips undertaken were on foot. Pedestrian infrastructure in the city, however, is extremely deficient. Peak-hour density around major railway stations exceeds four or five passengers per square metre. It is estimated that the infrastructure that facilitates walking to train stations must ideally be grown to five times its current capacity.

The notorious Mumbai traffic is known for high road fatalities as well. There were 403 reported fatalities in just 2019, which was the lowest in a decade as a result of focussed efforts, but still high enough to be concerning – pedestrians constitute more than 50 per cent of the total deaths.

More news from India

Funding secured for crucial Delhi rail corridor

It is hoped that the project will encourage commuters to settle in Delhi’s surrounding towns and cities, which would ease congestion and pollution in the capital.

Data foundation for futuristic Mobility

We now turn our attention to the extremely critical aspect of planning and decision making based on sound data points and its analysis. No less than 14 government departments are involved in regulating various aspects of mobility in Mumbai, with each collecting and managing data for their respective areas. Planning during the COVID-19 pandemic required synergies across various modes and the ability to collect and analyse data in real time.

Mumbai, however, relies on the CMP data that was released in 2016. This contains data accumulated throughout the preceding two years. Since then, the number of private vehicles has increased by 22 per cent on the roads, with the road network barely increasing. The use of dated data significantly dents the prospect of having an effective and responsive ability to plan in real time.

Another risk, as one study pointed out, is in relying on data without any context. This could lead to suboptimal outcomes. For instance, while the share of public transport is high, it is possible that some of the users aspire to travel on bikes or in cars but cannot afford it at this point. However, as their disposable income improves, a portion of this share may rely less on public transport and move to private vehicles.

The use of standard framework in data collection needs to be prioritised as these would enable better interoperability of data across different departments. Globally, the General Transit Feed Specification data framework is used, but in India only Delhi and Kochi utilise data in this format. A framework needs to be adopted that can be tailored for Mumbai’s specific needs.

The way forward

Throughout this article, we have attempted to draw attention to the pre-existing conditions that have severely hampered the response of the city’s transport systems to the COVID-19 induced crisis. There is an immediate need for a solution through concerted efforts to address these problems.

The CMP admits existing institutional arrangements for transport in the city are highly inadequate and there is a need for institutional strengthening, at regional as well as at Urban Local Body level. Creating a high functioning and effective unified transport authority is also a must. Mumbai could take inspiration from agencies such as Transport for London (TfL), which enables standard data gathering frameworks between different modes while also serving as a nodal authority for public transport planning and integrating last mile connectivity options. The new normal in Mumbai must not continue with the same fundamental problems in mobility and deserves a comprehensive overhaul.

Biographies

Related topics

Air Quality, Infrastructure & Urban Planning, Journey Planning, Mobility Services, Multimodality, Passenger Experience, Public Transport, Transport Governance & Policy

Related modes

Bikes & Scooters, Light Rail, Walking

Related cities

Mumbai

Related organisations

Central Road Research Institute (CRRI), The World Bank