How can new development persuade cities to part with the private car?

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Posted: 21 February 2020 | Erica Belcher - Centre for London | No comments yet

City developments and population change affect the infrastructure and transport planning of the future. Erica Belcher, Researcher at Centre for London, explains how mobility in London is experiencing this change and will continue to do so in the future.

The ways in which we move around cities in the future will be determined to by the choices we make now.

This has always been the case. In the 18th century, an extensive network of canals were built to ferry men, women and merchants in and out of the capital. In the mid-19th century, rail began to replace water as London’s modus operandi. And by the mid-20th century, London was ushering in the age of the private car. In response to rising car use in the 1980’s, the city encircled itself in a ring of motorway known as the M25. And urban planners built boroughs and neighbourhoods with the car at their centre, making navigation without one unthinkable.

But like other cities worldwide, we’re now experiencing the limits – and negative impacts – of this model of development. In London, road vehicles are the second largest contributors to greenhouse gas emissions. And in 2018, drivers lost 277 hours to traffic jams, costing £4.9 billion, or £1,680 per driver. Congestion, air pollution, the climate crisis, accidents on the roads and the inactivity crisis have forced London’s policymakers to rethink their ‘business as usual’ approach to roads and streets.

In London, road vehicles are the second largest contributors to greenhouse gas emissions

The current Mayor of London has set a bold aim for 80 per cent of all trips in London to be made on foot, by cycle or using public transport by 2041.

Achieving this step-change will take some work. Given the urgency of shifting to sustainable forms of transport and the speed of innovation within the sector, how should we design London’s neighbourhoods of the future? And what type of future should we be designing for?

A snapshot of recent development in London

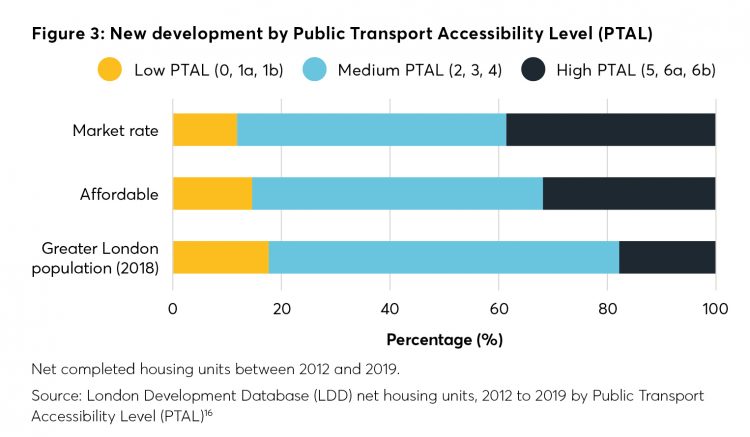

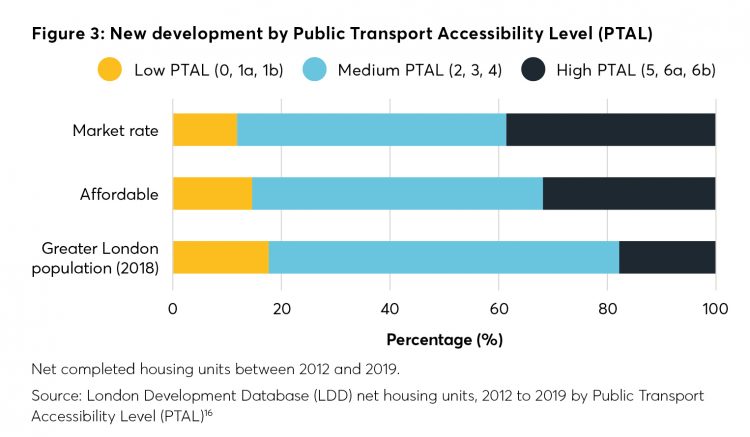

To accommodate the capital’s population growth, London’s 32 boroughs are planning for a 20 per cent growth of its housing stock over the next decade. This new development presents an opportunity to shape travel behaviour from the ground up. If London gets it right, then new neighbourhoods could pave the way for a revolutionary wave of sustainable urban mobility.

But we are at risk of finding ourselves stuck in the 1980s.

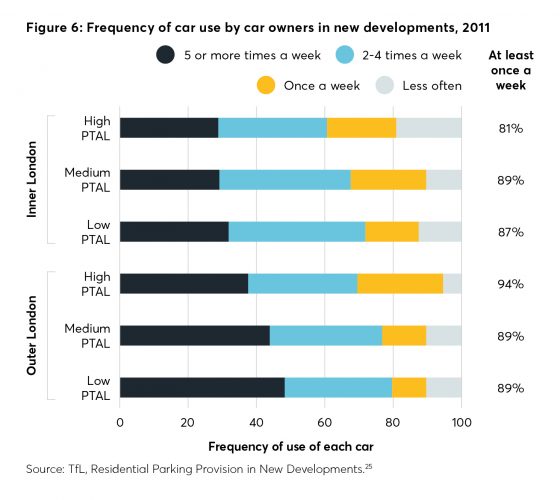

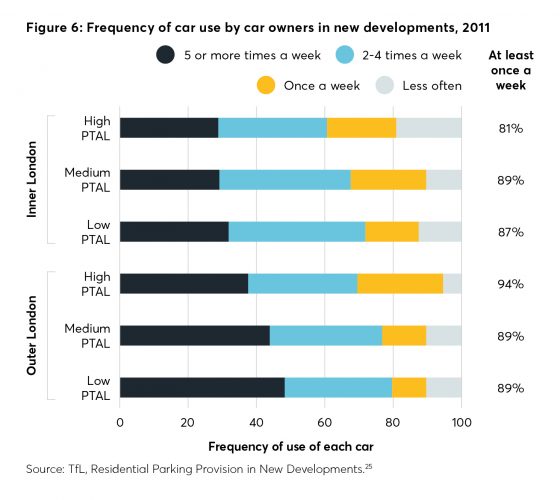

Unfortunately, despite being better connected by public transport, car ownership is still the norm in London’s new builds. New housing developments are also more likely include car parking than pre-existing homes. Unsurprisingly, the mantra of “if you build it, they will come” holds true, and residents of new developments are also more likely to own a car than the general London population. And many make good use of it. Even in the best-connected parts of London, 30 per cent of the residents interviewed used their own car between two and four times a week, and another 30 per cent use it practically every day.

But new neighbourhoods in London aren’t so generous when it comes to bike parking. A survey of 71 developments (all in west London) found that 45 per cent of the “bike parks” promised by developers were missing, and that none of those provided were user-friendly. For instance, many required cyclists to lift their bike up a steep ramp or to go through narrow doorways.

Unfortunately, despite being better connected by public transport, car ownership is still the norm in London’s new builds

To give credit where credit is due, London’s model of development means that financial contributions from developers are helping spur on public transport projects at the pan-London level. Developer contributions are part-funding Crossrail, tube line extensions, and cycling infrastructure across the capital. But somehow, despite choosing to concentrate housing near public transport, old habits die hard and some developers are creating new neighbourhoods that accommodates the private car more than existing neighbourhoods do.

Could technologies steer new development away from the private car? Developers and city planners need be wary of adopting transport innovations for innovation sake, and without careful consideration of the outcomes. Some innovations, such as app-based ride hailing, have been increasing congestion and car use. Similarly, there’s been a lot of excitement around autonomous vehicles, but no roadmap has been designed to explain how they could be integrated into complex urban environments. There’s also a lingering uncertainty as to whether they might increase private vehicle use, exacerbating the problems we experience today.

But some technologies are promising alternatives to the private car and could be harnessed in new developments: e-bikes and e-scooters increase the range of traditional journeys, but use much less energy and space than electric cars. New developments are an opportunity to make their use safe and convenient.

As well as newer forms of micromobility, the capital’s public transport network has proved to be the tried and tested method of moving Londoners around efficiently, though its capacity is bursting at the seams.

How can London facilitate new urban mobility?

London needs an approach to transport planning in new developments that is rooted in evidence, led by policy, and that champions sustainable travel. In a recent report, Centre for London made the case for a ‘New Urban Mobility’: harnessing technology to enable active travel, public transport use, the cleanest vehicle technology and minimal use of private cars.

We believe that the potential benefits of innovations in mobility won’t be realised if London fails to establish a strategic vision. Our research devised principles for the UK capital and other global cities to follow if they are to reap the full benefits of new urban mobility:

- Master plans should be based on active travel and public transport, by tying together street patterns, and locating public transport and public amenities within close reach

- Transport for London and the Department for Transport should part fund mobility hubs, so dropping off your e-bike to jump on the tube, or changing from train to bus, is quick and easy

- London boroughs should create ‘New Urban Mobility zones’ where they will work closely with developers to trial new modes of travel and encourage residents to move away from the private car

- Developers should limit parking provision, locate it some distance from residents’ front doors, and provide quality electric charging infrastructure

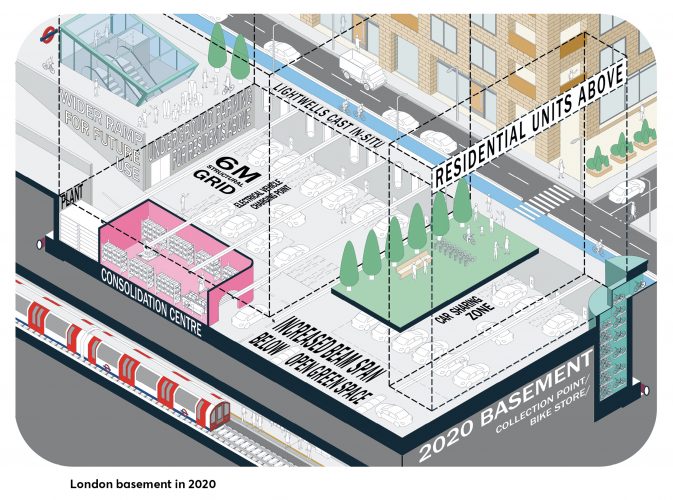

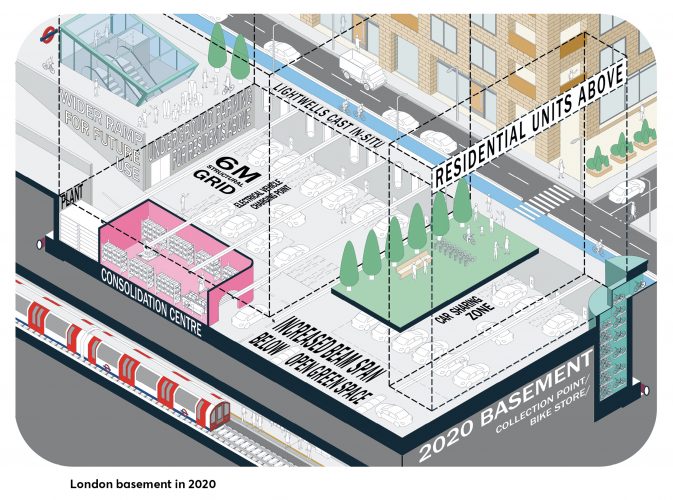

- Any car parking built should be convertible to other uses. Car parking build today risks becoming obsolescent in places where public transport improvements are planned, or where walking and cycling enhancements and new technologies could entice more residents to choose active travel. Hawkins\Brown have modelled how a basement car park can be made convertible. By introducing higher ceilings, light wells and reducing the load above ground.

Image source: Hawkins\Brown

What does development designed with new urban mobility in mind look like?

One example is the Merwede Canal Area (“Merwedekanaalzone”) in the Dutch city of Utrecht, a 400,000sqm new development.

Initial plans show that everything within the neighbourhood will be within walking and cycling distance – including the train station – making private car use largely redundant. Multimodal shared hubs – the project’s pièce de résistance – will provide bike sharing drop off, and pick-up for parcels and online delivery.

As well as newer forms of micromobility, the capital’s public transport network has proved to be the tried and tested method of moving Londoners around efficiently, though its capacity is bursting at the seams

64 kilometres north of Utrecht lies Circular Buiksloterham. This small development in the North of Amsterdam is a living experiment in circular city-making. The brownfield offers an unusually blank slate. It’s near to, yet disconnected from, the city writ large. When complete, the neighbourhood will feature buildings designed for disassembly, flexible zoning and a Direct Current (DC) smart-grid. Electric-vehicle car sharing, solar bike paths (covered by a roof with half solar panels, half vegetation) and a communal bike repair shop (complete with 3D printer to print custom parts) make the sustainable development positively futuristic.

And in the French capital, sits MKNO, on a former industrial site along the eastern canal d’Ourcq in Paris-Bogigny. Like Merwede, the centrepiece of MKNO is a 1000 m2 new mobility incubator (or “Garage Bleu”) which will trail new modes of travel and, like Buiksloterham, the buildings will incorporate a flexible, modular design.

Barriers to new urban mobility

London too can deliver exemplary, sustainable developments. But to encourage all developers to embrace New Urban Mobility, London’s local authorities need to prioritise it in both strategic planning and development control. Developers should embrace adaptability into their designs especially when building car parking – and understand that designing for New Urban Mobility can be good for place and for property value.

Biography

Erica Belcher is Researcher at Centre for London and has co-authored reports on road user charging, city planning and inequality and social mobility. Erica’s research interests chiefly include urban transport planning and the built environment, and she has a MSc in Comparative Politics from the London School of Economics.

Related topics

Infrastructure & Urban Planning, Mobility Services, Passenger Accessibility, Public Transport, Sustainable Urban Transport, Transport Governance & Policy

Related cities

London

Related organisations

Centre for London