An Indian experiment with free transit

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Posted: 16 December 2019 | Dominic Mathew, Dona Mathew | No comments yet

On the 29 October 2019, the Delhi government operationalised free public transit for all women in the Indian capital – more than a third of total ridership. Dona Mathew and Dominic Mathew explore how and why the state has implemented such a system.

On a slightly chilly and smoggy mid-November day in New Delhi, India, a group of men board a crowded Delhi Transport Corporation bus, grumbling about the increased number of women riding alone or accompanied by their children or parents. Their barbs include comments on “women out for joyrides with their kids” and “shouldn’t they be taking care of the household”. Other than being a window into a patriarchal mindset, it also highlighted trip-chaining among women, linking short trips for shopping, day-care or taking care of the elderly in between a home and work trip.

The Delhi government operationalised free public transit for all women in the Indian capital on 29 October, the day of Bhai Dooj – a Hindu festival that celebrates the love between a brother and sister. An estimated 2.2 million women use the state’s bus and mass rapid transit network everyday, constituting more than a third the total ridership. Free transportation for women, in a city of 19 million residents where 30 per cent of all trips are made on public transit, will have a tremendous spillover effect on its economy.

Figure 1: People waiting to board a Delhi Transport Corporation (DTC) bus.

So how and why did Delhi do it? Why did the state opt to do away with fares that are 65 per cent of revenues for the Delhi Transport Corporation buses? The reasons are economics, safety concerns and politics. As per the 2016 National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) data, Delhi has one of the lowest numbers of female workforce participation (only 11.7 per cent of the workforce in Delhi are women). Combined with a dismal gender ratio, economic mobility for women in the state is severely restricted.Compare this with American cities, where the clamour for free transit has picked up every now and then. A recent three-day long public summit in Cleveland identified transportation as one of the biggest barriers preventing the city from rising, with free transit being a proposed solution. It is music to the ears of riders and, if backed by good quality services, can reinvigorate a city, but who pays the massive $51 million shortfall, the 16 per cent of revenues that fares make up for the Greater Cleveland RTA? In sharp contrast to Delhi and similar cities in ‘developing’ countries, where public transit can account for 30-40 per cent of trips, the car rules the road in America. Until strong political will and alternative financing for a sustainable free transit system is established, it is a tall order for any city to implement.

Free transportation for women, in a city of 19 million residents where 30 per cent of all trips are made on public transit, will have a tremendous spillover effect on its economy

Cost can be the biggest barrier of all. A monthly pass across the air-conditioned and non-airconditioned buses can range from $11 to $15 – a huge chunk of one’s income for a state where more than half the population’s monthly per capita expenditure is below $42. The same goes for Delhi Metro users, who in 15 years have seen a 400 per cent increase in maximum fares. At this point, only buses are part of the scheme, at an annual cost of $42 million, but the Delhi government plans on footing a massive $166 million bill to extend this to the metro network. Delhi Metro is operated jointly by the federal and state government, which has slowed the progress of the programme rollout. To be a true success though, the idea that free transit will lead to women taking up jobs that were earlier inaccessible because of cost-prohibitive fares, will need to be bolstered with aligned workforce policies.

Women’s safety within the public transport system is a huge issue in Indian cities. New Delhi’s high rate of crime against women and that women in Delhi feel unsafe inside public transport or waiting for it is well documented. This sense of insecurity comes from harassment faced every day, including instances of unwanted touching, gesturing and staring. The 2012 gang-rape and murder of a young woman in a bus in Delhi highlighted how unsafe and deadly public spaces are for women. Though the Delhi Government introduced Civil Defense Volunteers on buses – youth trained to intervene in any untoward incidents – improving public transport from a safety perspective requires a long-term vision that combines sensitisation, capacity-building and punitive measures.

The direct impact of free travel will encourage more women to use public transport, increasing their presence in public spaces. A core premise of safety initiatives is to increase the visibility of women in public spaces to encourage other women to use public spaces and contribute as equal citizens in the economy. However, concessionary travel in itself is not enough to ensure safety for women. Additional interventions – like better street lighting, well-lit bus stops in prominent spaces with lots of activity and last-mile connectivity – are necessary for providing safe public spaces for women.

Ultimately, this decision is a political one. The Aam Aadmi Party (Party of the Common Man) were surprise victors in a David-Goliath battle during the 2015 Delhi state elections. The next elections are in early 2020, just in time for goodwill from this decision to translate into votes. Political opponents and critics ask why the scheme is only for women if economics is a reason. Why not provide it for all from low-income groups? Also, terming this as an election stunt means people don’t believe it is a long-term plan, and many anticipate the scheme to end after the 2020 elections.

A core premise of safety initiatives is to increase the visibility of women in public spaces to encourage other women to use public spaces and contribute as equal citizens in the economy

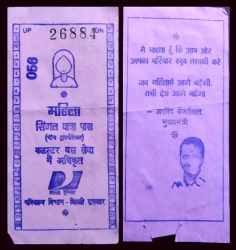

Figure 2: Pink tickets issued to women who want to travel for free, each has a 15 cents value subsidised by the Delhi government.

That does not mean that free transit cannot be a financially sustainable decision. On a smaller scale, Seattle runs the $7 million Orca Opportunity programme that provides free bus passes for 16,000 public high school students, Seattle College students and residents living in Seattle Housing Authority properties. The programme uses Seattle Transportation Benefit District (STBD) funds, a measure that includes a $60 vehicle license fee and a 0.1 per cent sales tax.

The Estonian capital Tallinn introduced free public transport in 2013 after a public poll. The municipality gets a €1,000 share of resident income taxes and charges a one-time €2 fee for a green card. Last year, 11 out of 15 counties in Estonia followed suit, with the caveat that tourists and visitors pay for fares. Luxembourg has pledged to make public transport free across the country in 2020, though transit is heavily subsidised already. Downtown free zones have been tried, tested and, in some cases, abandoned in American cities like Portland, Seattle, Salt Lake City, Columbus and Pittsburgh. Kansas City, Missouri in early December 2019, became the first major American city to make public transit free systemwide. The city council unanimously voted for ‘Zero Fare Transit’ but is still working on details to recoup the $8 million loss in fares. As public agencies and communities explore new forms of mobility and stock their arsenals to increase economic mobility and ridership, free fares could be one of the tools in the toolbox, along with affordable housing, better land-use and workforce development policies.

Biography

Dona Mathew is a researcher based in New Delhi working with an intergovernmental organisation. A lawyer by profession, her areas of interest are gender rights and criminal law.

Dominic Mathew is an architect-planner who works on addressing mobility and job-access challenges in Northeast Ohio with an economic development collaborative, the Fund for Our Economic Future. He manages an open mobility competition, the Paradox Prize, investing $1 million in 15 job access pilots.

Related topics

Passenger Accessibility, Passenger Experience, Public Transport, Security & Crime, Vehicle & Passenger Safety

Related cities

New Delhi

Related organisations

Delhi Transport Corporation (DTC)