Is now the time for open-loop transit in the United States?

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Posted: 11 June 2019 | John Elliott - Consult Hyperion, Simon Laker - Consult Hyperion | 1 comment

Simon Laker and John Elliott at Consult Hyperion explain how, after more than a decade of trials and poorly-received launches, open-loop transit payments are now expected to gain significant traction in the U.S.

Open loop refers to payments that can be made at most retail outlets using international standards, while closed loop means it only works with specific retailers, usually based on proprietary technology.

Open-loop transit payments generally refer to the use of bank-issued contactless credit and debit cards instead of closed-loop transit authority/ operator alternatives, such as the MetroCard in New York City or the Bay Area’s Clipper Card.

The history of open-loop payments in the U.S.

The first open-loop transit trials (using contactless magstripe cards) took place in the United States in:

- 2006: a collaboration in NYC between Mastercard, Citibank and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA)1 where several stations on the Lexington line were fitted with contactless readers to accept fare payments. The trial, which lasted just under a year, required Citi card holders to pre-register for the service in order to be authenticated fast enough when they tapped in.

- 2010: a second, broader trial1 in which the MTA combined with neighbouring agencies, the Port Authority and New Jersey Transit. During this pilot, 17,000 Mastercard and Visa cardholders were able to use their contactless payment cards to tap on multiple bus and train routes across the region. Despite feedback on both pilots being positive from customers2, the MTA project stalled.

In Utah, the UTA launched a new high-tech fare-collection system in January 20093 that was capable of accepting bank-issued credit and debit contactless chip cards alongside their own closed-loop Farepay card. In August 2013, the Ventra system was launched by the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA)4, a fully open-loop system which also featured an agency-issued card that could operate closed-loop within the Ventra network and had the option of open-loop for other merchants should the cardholder wish to activate the prepaid capability of the card.

In 2017, TriMet in Portland launched the Hop system5, allowing users to tap their Apple or Google Pay devices to gain access to the system or use the closed-loop Hop Card. TriMet have expanded this capability by allowing Android users to load their Hop Card into the Google Wallet.

However, today, CTA’s Ventra and TriMet’s Hop are the only transit systems accepting open-loop payments in the U.S. In April 2018, the UTA stopped open-loop acceptance citing “new federal regulations” and the cost of maintaining infrastructure compliance for as few as one per cent of their ridership who were using open-loop contactless.

The fundamental reason U.S. transit agencies have been hesitant to deliver since the first launches and pilots has been the time it takes to authenticate the card when it is tapped at the gate. Prior to contactless EMV, the only way the agency knew they were definitely not seeing a fraudulent card, and that they were going to get paid, was to conduct a full online authorisation to the card issuer. It is not possible to do this in less than a second. With contactless EMV, it is possible to know in under half a second that a card is genuine at the gate, which can significantly increase the chance of the transit operator being paid if they let the passenger travel.

Not all open-loop contactless cards are the same

The U.S. has been a tough market for transit agencies to deliver successful open-loop systems into, as banks have not been in step with these ambitions. The U.S. was late to adopt bank cards with chips because they did not have the same fraud issues that other markets did. Instead, they continued to use the legacy magstripe payment cards. As chip cards limited fraud elsewhere in the world, the fraud migrated to the U.S. and chip cards started to be introduced.

However, the first contactless cards introduced in the U.S. in 2005 merely replicated the magstripe data on the chip (let’s call these cards ‘contactless magstripe’) and thereby did not deliver the benefits of the increased speed of transactions conducted offline (rather than having to go online to the card issuer for authentication) and better risk management. Both of these benefits were needed for the transit environment where passengers need to board quickly. Cardholders saw no benefit in the contactless magstripe cards and continued to swipe the magstripe on the card rather than tap the chip, causing disillusionment by retail merchants who had invested heavily in contactless acceptance terminals. In other markets around the world, the ‘chip-and-PIN’ cards following the international standard known as EMV, had been successful in limiting fraud.

The next move was to issue contactless bank cards meeting the EMV standard (let’s call these ‘contactless EMV’) that allows the payment terminal to use the chip on the card to manage risk and did not always require a PIN to be entered, therefore making transactions fast and appealing for low-value consumer payments. Contactless EMV cards were ideal for transit whereas contactless magstripe were not.

How else is the present day different?

In 2015, the ‘EMV liability shift’ in the U.S. drove payments from being magstripe card based towards the use of standard EMV chip cards with merchants incentivised to upgrade their point-of-sale terminals to be EMV-compliant to avoid liability for payment fraud. A side-benefit of this was that 95 per cent of all terminals shipped in this process were capable of contactless with at least 50 per cent enabled6. Once the contactless terminals were in place, the U.S. banks were motivated to issue contactless EMV cards. Major transit agencies in the northwest and northeast of the U.S. saw the opportunity to engage and move forward with plans to accept open-loop transit payments with contactless EMV rather than contactless magstripe.

All of the major agencies in the States have been working closely with the payment brands – American Express, Discover, Mastercard and Visa – through the U.S. Payment Forum to define an operational and risk model that works for the U.S. market. These models bear a close resemblance to the core models Consult Hyperion helped develop with Transport for London, Visa and Mastercard back in 2009/10. One significant change to the London model is that communication speeds and system architectures for open-loop systems are better 10 years on, so the risk models do not necessarily require deny lists to be held on every transit validator.

With the retail environment set up for contactless, and the major U.S. transit agencies moving forward with plans, what about the cards in consumer hands? Until recently, the only contactless EMV payments available in the U.S. were through Apple, Google or Samsung Pay on mobile phones, because the banks were not issuing contactless EMV cards. During the first reissuance cycle of EMV cards (typically every three years for bank cards) in the U.S. market, many issuers are looking to upgrade to dual-interface cards (contact and contactless), the most significant announcement being Chase at the end of 20187.

We expect the first U.S. open-loop transit launch since the 2015 liability shift to be in 2019 in New York City, with Boston close behind. San Diego recently announced their intention to follow suit and we are sure others will follow.

It seems that the time is right for the U.S., but what are the benefits of open-loop transit and why are the big agencies working so hard to deliver it?

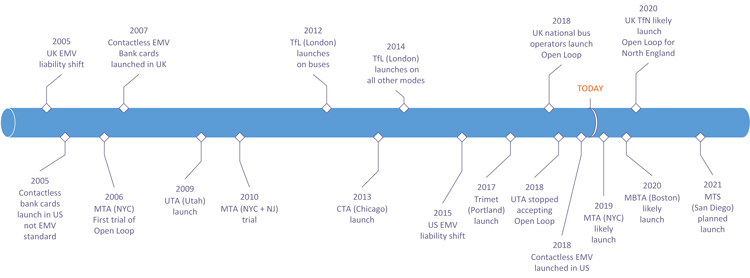

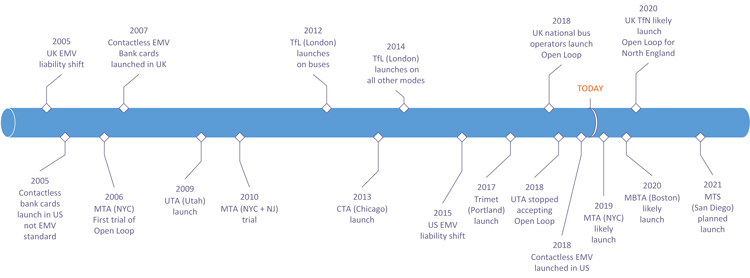

The route to open loop: UK (top) versus U.S. (bottom)

The benefits of open-loop transit

The benefits of open-loop are simple. Firstly, the old, closed-loop, card-based systems are expensive to operate; according to TfL, as much as 14 pence in every pound collected is spent on operating the Oyster system8, whereas, by comparison, open loop can be operated for as little as 10 pence which, given revenues of over £3 billion, amounts to savings of over £100 million.

There is also a safety concern in some established transit networks, with customers queuing to reload pre-paid fare media at busy times. This is particularly evident in big systems like New York and London but is solved with open loop as there is no need for vending machines, meaning transit agencies can save money on capital and maintenance costs.

Without the need to manage a transit card, customers can simply tap their bankcard on the validator and be charged the correct amount for their journey. For visitors, there is no need to try to understand complex fare costs and budget accordingly – the right amount is taken and there is no residual value left on the card once the trip is over.

Is there a down side?

While it may appear that open loop is beneficial for all, there are some elements of these systems that need to be carefully considered to ensure they are inclusive for all. For the majority, using the credit or debit card in their wallets (physical or mobile) makes sense, but for those that don’t have a bank card, don’t wish to use one or who simply want to remain anonymous, using a transit agency-issued alternative (e.g. closed-loop card or app) has continued benefits.

These cases require the transit agency to continue to issue a credential of their own, but careful selection of the right technology and the way it operates in the system can still allow the transit agency to realise cost savings over the card-based closed-loop system. For example, the Key Card issued by SEPTA (South-Eastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority) is Mastercard branded but can only be used on the transit system in Philadelphia until the cardholder enables a prepaid account feature which allows use anywhere that Mastercard is accepted.

Another issue U.S. operators have to manage is the integration of pre-tax transit benefits programmes that are often issued on prepaid debit cards, such as the Commuter Benefits Plan from Benefit Resource Inc. These cards can only be used for public transportation and therefore transit value needs to be loaded to a prepaid account or pass product before they can be used.

Finally, the kinds of systems deployed in London and being implemented in New York and Boston are very expensive to build, usually requiring government funding and large travelling populations to justify them. Not all cities, indeed, not all countries, can afford them, and, frankly, their complexity is not needed if you are a single operator of a single mode without aggregated journey fare capping. The UK is seeing cheaper, simpler systems being used by the national bus companies to allow them to accept open-loop payments. Maybe this trend will also be adopted by U.S. transport operators too.

References

- https://www.americanbanker.com/news/mc-citi-to-test-contactless-transit-card

- https://www.fastcompany.com/1813345/exclusive-look-inside-mta-mastercard-paypass-pilot-17000-nyc-customers-six-months

- https://newsroom.mastercard.com/2011/08/24/new-methods-of-paying-for-public-transport/

- https://www.deseretnews.com/article/705273709/UTA-tapping-into-high-tech-fare-collection.html

- https://www.transitchicago.com/cta–pace-announce-ventra-launch-date-for-select-customers-more-details-on-transition-to-new-modern-fare-payment-system/

- http://news.trimet.org/2017/07/time-to-hop-on-board-as-trimet-c-tran-and-portland-streetcar-officially-launch-hop-fastpass-your-new-ticket-to-ride/

- https://www.digitaltransactions.net/visa-begins-a-u-s-contactless-payments-push-again-this-time-the-pos-hardware-is-in-place/

- https://www.creditcards.com/credit-card-news/contactless-cards-get-crucial-boost-chase.php

- https://www.computerworlduk.com/it-leadership/transport-for-london-ticketing-chief-dubious-about-mobile-nfc-3426521/

Biographies

Related topics

Ticketing & Payments

Issue

Issue 1 2019

Related cities

United States of America

Related organisations

Consult Hyperion

Related people

John Elliott, Simon Laker

This is nice, but it still seems way behind systems like those in China where you can pay at most retailers, transit agencies, and micromobility vendors (Didi/Uber/Lyft, scooters/bikes) via a QR code generated in WeChat Pay. Why isn’t such a universal system like this taking hold in the US? Especially since it is platform independent and not Android or iPhone specific.