India’s shift from conventional transport to electric vehicles

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Posted: 15 November 2018 | Sunil Kumar Agrawal - NTPC Ltd | 1 comment

Sunil Kumar Agrawal, from NTPC Ltd, discusses India’s automobile industry and its current position in the electric vehicle market, detailing how the country requires consistent and strong policy frameworks to continue developing.

The Indian automobile industry is the fourth largest in the world and sales are still increasing with a CAGR of 7.01 per cent annually; reaching 4.02 million units (excluding two wheelers) in 2017.

India’s automobile industry is expected to reach $250-$280 billion by 2026 and demonstrates a high potential of growth. The sector remains in a very early stage of development with non-motorised and public transportation still largely representing the majority of trips (approximately 66 per cent in 2007). Even though the Indian automobile sector has shown a consistent growth for a long time, the number of automobile owners per capita has remained very low with only 50 vehicles per 1,000 people, in comparison to 231 vehicles per 1,000 people in China and 910 in the U.S.

This brings great opportunity, but at the same time, presents a great challenge for India. Alongside this, the country is already dealing with an existing automobile stress in terms of carbon emissions and energy security.

As per a WHO report in 2018, 14 of the world’s 15 most polluted cities are Indian. In 2014, Delhi, India’s capital, became the most polluted city in the world. As per the Global Burden of Disease comparative risk assessment for 2015, air pollution exposure contributed to approximately 1.8 million premature deaths and 49 million disabilities adjusted life-years (DALYs) lost, which makes air pollution a top contributor of ill health in India.

The transport sector is one of the biggest contributors of air pollution in India. Vehicles predominantly run on fossil fuels and as a result, Indian cities suffer from extremely high levels of urban air pollution particularly in the form of CO2, SO2, NO2, PM (Particulate Matter) and RSPM (Respirable Suspended Particulate Matter).

Moreover, crude oil imposes a big burden on India’s import bill. India imported 83 per cent of its crude oil in 2015-16, which costed around INR 4,160 billion. These figures illustrate the need for a mobility transformation. A Niti Aayog report in 2017 showed that India could reduce 64 per cent of anticipated passenger-mobility demands, and 37 per cent of carbon emissions in 2030, by pursuing a shared, electric and connected mobility.

This would result in a reduction of 156 million tonnes of oil equivalent (Mtoe) in diesel and petrol consumption for that year. At $52/bbl of crude, this would imply a net savings of roughly $60 billion in 2030.

India’s current electric vehicle status

Table 1: Electric vehicle and infrastructure status. Credit: Global EV outlook 2018

India has been a laggard in the global race towards the electrification of automobiles, with no clear guiding policy, unlike China, who offered hefty subsidies and incentives to promote battery-powered cars in its efforts to reduce dependence on oil imports.

In the absence of clear government support, the nascent push towards electric mobility is largely being driven by personal choice. Indian consumers currently have roughly 10 electric/hybrid car variants to choose from, compared to 54 in the U.S. and over 100 in China.

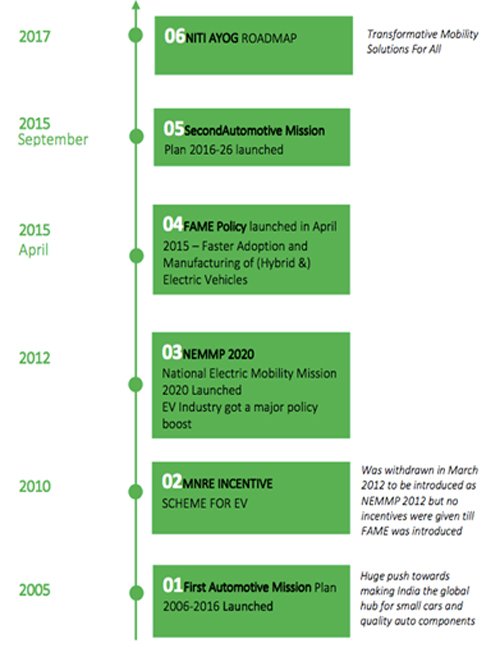

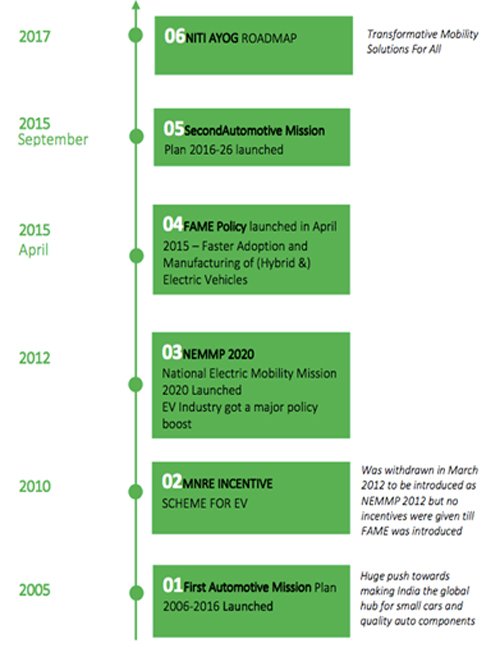

Although the government has taken some steps in recent years (some which are summarised in Figure 1), the short-term visionary steps and inconsistency in decision making have been the primary roadblocks in electric vehicle adoption in India.

An Indian think tank revised its electric vehicle penetration target from 100 per cent of vehicle sales to 30 per cent within one year of announcement. As of now, India has no formal policy announcements or notifications on electric vehicles.

On a brighter note, some of the government incentive schemes have certainly shown some positive outcomes in the country’s electric vehicle sales. National Electric Mobility Mission Plan (NEMMP) 2020 aims to promote hybrid and electric vehicles (Government of India, 2012), resulting in the development of the Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of (Hybrid and) Electric Vehicles (FAME), which incentivised the purchase of electric vehicles. Under the FAME scheme, the government is expected to spend around INR 140 billion, which includes incentives for the customers to purchase electric vehicles and incentives for the manufacturers to research them. In early 2018, an interim arrangement was set up to enable charging stations to operate without a license, potentially improving the conditions of electric vehicle charging stations (First Post, 2018).

India’s infrastructure requirement to support electric vehicles

Other than government policies and incentives, shared infrastructure development is one of the major requirements for facilitating electric vehicle adoption in India. Shared infrastructure demand consists of two major elements: first is electricity demand, and second is public-charging demand.

Figure 1: Indian electric vehicle policies. Credit: Indian electric vehicle story, Innovation Norway

The electricity sector of India

The installed power generation capacity of India is large enough (344.7 GW as on 31 August 2018, as per Ministry report, Government of India) to cater to the demand generated by electric vehicles. In fact, the average plant load factor of the country was only 60.67 per cent in 2017-18, which means about 40.3 per cent of the capacity was unutilised. A demand generation through electric vehicles will be a boost for the power generation industry. As per the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) report, 100 per cent battery electric vehicle sales would add six per cent to the peak electricity demand of the country.

The only concern is the present energy mix of the country. India’s power mix is primarily driven by coal-based powerplants, which generated 75.9 per cent of the total country’s electricity in 2017-18. With the low-average efficiency of Indian coal powerplants, electric vehicles would not provide the much-needed environmental benefits but shift the pollution from cities to hinterlands. Therefore, the Indian power sector will have to increase the efficiency of its power plant or bring more greener options such as solar, wind and large hydro into its energy portfolio.

The Indian government has set up a target of 175GW of renewal energy capacity by 2022. If India achieves this target and supplies the power to electric vehicles through renewable sources, then it would result in a sustainable solution.

The Indian power distribution sector brings a major setback in the development of electric vehicle infrastructure. The present financial situation of state electricity boards is not stable. This is mainly due to uneconomic tariffs for agriculture, high T&D losses (which often disguise large-scale theft), and low billing and collection efficiency. Electric vehicle charging infrastructure would require a strong distribution grid network that can support the high voltage supply demand, which would be a great challenge with the existing distribution infrastructure. It would require a major overhaul of the distribution system and hence, a large investment.

Public charging infrastructure in India

As shown in Table 1, there were only 222 publicly-accessible chargers in India in 2017, in comparison to 130,508 in China, 32,976 in Netherland and 22,213 in Germany in the same year (EV outlook, 2018).

In recent years, the government of India has taken some serious steps to increase the pace of public charging facility installation. These steps include treating electric vehicle charging as a ‘service’ under the Electricity Act, 2003, the opening of the electric vehicle charging market for all and introducing dynamic pricing with time-of-day tariffs.

India recently released a draft notification for socket outlets or vehicle connectors to be used in electric vehicle chargers. Draft ‘Bharat EV charger’ standards specify the charging standard for India.

Electric vehicle charging policies

Aside from national targets and electric vehicle policies, some Indian states have come up with their own to support electric vehicle growth. The Kerala government has set a target of putting 10 million electric vehicles on the road by 2022. The state rolled out an electric vehicle policy (EVP) studded with tax holidays and the creation of common-charging infrastructure.

Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Telangana and Uttar Pradesh have already announced official policies regarding electric vehicles, and other states are in the process of drafting similar documents.

The state of Karnataka is also aggressively incentivising the production of electric vehicles, establishing a target of $4.83 billion in investments that will help generate 55,000 jobs.

State governments are setting electricity tariff policies for charging electric vehicles. The Delhi state electricity regulatory commission has set the electricity tariff (TARIFF ORDER 2017/18) at INR 5.50/kWh (supply at LT) and INR 5/kWh (supply at HT). Andhra Pradesh state DISCOM (Distribution company) has filed a petition for a tariff order for electric vehicle category tariff: INR 6.95/kWh (Bloomberg New Energy Finance Report). The state of Maharashtra has planned to set up a special electricity tariff for electric vehicle charging. These initiatives will certainly reduce the cost of ownership for electric vehicles and speed up the adoption process.

Conclusion

High levels of vehicle pollution and the burden of the import oil bill put huge pressures on India to shift from conventional vehicles to electric vehicles, whilst presenting the automobile sector with a great opportunity. Growth of electric vehicles in India has been long held back in comparison to other countries due to poor government policies and infrastructure support. Recent changes in policies represent good progress, but India requires faster, consistent and stronger policy frameworks to continue improving.

Biography

Related topics

Air Quality, Alternative Power, Fleet Management & Maintenance, Infrastructure & Urban Planning, Sustainable Urban Transport, Transport Governance & Policy

Related cities

India

Related organisations

NTPC Ltd

Related people

Sunil Kumar Agrawal

The state of Karnataka is also aggressively incentivizing the production of electric vehicles, establishing a target of $4.83 billion in investments that will help generate 55,000 jobs.