Forecasting what lies ahead in 2022 for technology-enabled mobility

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Posted: 21 April 2022 | Carol Schweiger - Schweiger Consulting | No comments yet

Carol Schweiger, Intelligent Transport Advisory Board Member and President of Schweiger Consulting LLC, shares her thoughts on what the future looks like for technology-enabled mobility, and has identified five key strategies that will become significant in this field throughout the remainder of 2022 – with a particular focus on developments within MaaS.

By now you have probably read numerous articles predicting what will happen in the area of technology-enabled mobility in 2022. While that is the subject of this article, I recognise that there is no one silver bullet that will address all of our current transportation challenges. For example, many articles mention electrification as a solution to some of those challenges. Although electrification is definitely one of many solutions, it is not likely to address traffic congestion or changing travel behaviour toward public transport.

Five key strategies for 2022

In 2022, there are five strategies that will become significant in technology-enabled mobility (not in any particular order).

Commingled transport

First, we will see many agencies beginning to explore or implement commingled transport services. Currently, commingling is defined as merging demand-response transport or paratransit with other mobility on-demand services – such as micro-transit – into one service. One reason for considering commingling is to reduce the typically high cost of paratransit services (e.g., in the U.S., the Americans with Disabilities Act [ADA] requires paratransit services that are complementary to fixed-route services).

By using new scheduling and dispatching software, commingling is now possible and is being deployed in a variety of locations, including Lincoln, Nebraska in the U.S., StarTran, the public transport agency in Lincoln, uses the same fleet of vehicles and drivers to provide both paratransit and micro-transit services. “The pooled ridership brings together a diverse group of people, ultimately bringing the community closer together while maximising operational efficiencies and rider experiences.”1 Another example of commingling services is being provided by Citibus in Lubbock, Texas.

Commingling is defined as merging demand-response transport or paratransit with other mobility on-demand services – such as micro-transit – into one service.

Equity, diversity, accessibility and inclusion

Second, the keen interest in addressing equity, diversity, accessibility and inclusion (EDAI) in technology-enabled mobility will expand to conducting equity impact assessments, defining key equity dimensions and metrics, and developing mobility equity frameworks.

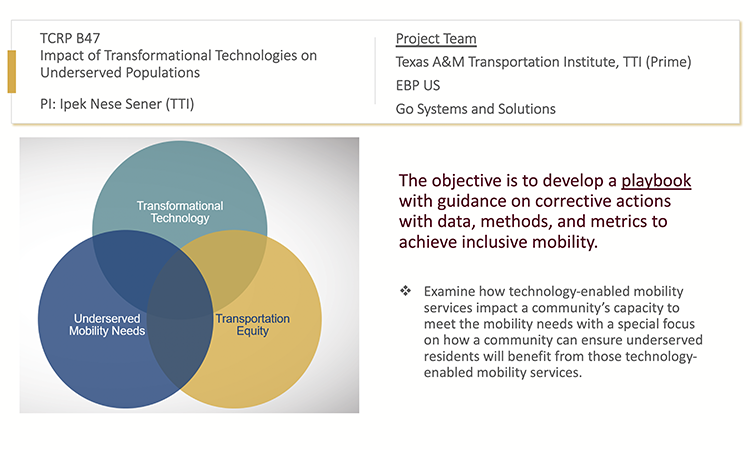

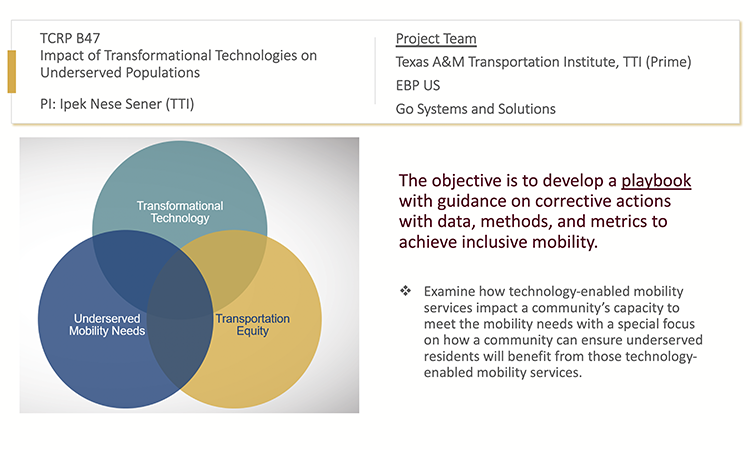

One unique project in this area is the development of an equity assessment tool as part of the U.S. Transportation Research Board’s (TRB’s) Transit Cooperative Research Project (TCRP) B-47: Impact of Transformational Technologies on Underserved Populations. In this project, four dimensions of equity for new mobility services are identified:

- Firms, markets and competition

- Regulations and subsidies

- Geographies and jurisdictions

- Stakeholder groups.

Also, the project identified barriers for a variety of mobility services among underserved groups, and then looked at the usage of these services if the barriers were removed. This project, which runs through to March 2023, is developing a playbook with guidance on corrective actions with data, methods and metrics to achieve inclusive mobility, as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 1. TCRP Project B-47: Impact of transformational technologies on underserved populations.

At the 2021 Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) World Congress held in Hamburg, Germany, Professor Sarah Sharples, Chief Scientific Adviser at the United Kingdom Department for Transport (DfT), described an equality impact assessment (EIA), as well as the future of equity in ITS, which consists of these four approaches:

- Embedding thinking about EIAs as early in the technology development process as possible

- Working with diverse groups to deliver design solutions

- Addressing areas where there may be a tension between equalities and other factors (e.g., e-scooters, on street chargers)

- Recognising the breadth of characteristics around inclusion (e.g., geographical distribution of interventions).

Another example of incorporating EDAI in a technology-enabled mobility project was in the 4All project conducted by the Swedish National Road and Transport Research Institute, which studied self-driving buses. This project examined how to define and treat accessibility, and the willingness and ability to use self-driving vehicles, as well as how the EDAI lessons learned from the trial in Vallastaden, Linköping, could be applied to other locations.

Mobility-as-a-Service

Third, 2022 is likely to see several of the challenges associated with Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) being addressed and overcome. Five key MaaS challenges include:

- Required collaboration across various organisations – particularly, the complexity of bringing together the large number of different stakeholders

- Approaches to enable businesses and policies from data and data sharing

- Lack of trust and willingness to share data between and among the MaaS actors

- Data sharing leaves the actors exposed but does not guarantee an increased number of trips or revenues

- It is not easy to distribute or share public subsidies/revenues across the value chain when it includes both public and commercial actors.

One approach that addresses several of these challenges is using existing MaaS standards, such as the TOMP-API, which is the result of a collaborative effort in the Netherlands to create a standardised language for the technical communication between Transport Operators and MaaS Providers (TOMP) within any MaaS ecosystem. Other approaches include new MaaS business models and architectures – many of which were introduced during the 2021 ITS World Congress in Hamburg, Germany – such as Mobility Tokens, MaaS Linking-of-Services (LOS) concept, User Centered Trusts (UCTs) and a Unified Mobility Management Model.3

2022 is likely to see several of the challenges associated with Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) being addressed and overcome.

Behavioural science in MaaS

Fourth, there will be a much-expanded exploration and application of behavioural science in MaaS. Since MaaS is touted as a way to impact travel behaviour, it is surprising that only very recently have researchers and practitioners recognised that behavioural science could be extremely useful in designing MaaS systems. Fortunately, discussions about utilising behavioural science to design MaaS are now happening more than ever before.

Jana Sochor, one of the most prominent MaaS researchers, identifies several reasons why behavioural science should be incorporated into MaaS design: “It is important to remember that a lot is being asked of potential MaaS users, as integrated mobility services can be difficult to grasp, especially while they remain largely unobservable and untestable.

“Study participants or potential customers must not only 1) try to understand the new service concept in general (MaaS), but they must also 2) try to comprehend a particular manifestation of MaaS with a very specific, detailed service offer (and, in the case of a theoretical study, a service they cannot observe or test), while they also need to 3) reflect (probably for the first time) on their transport needs and use, 4) estimate how well [the service] may or may not match their transport needs and use (also considering that use patterns may change due to using the service), and 5) decide whether or not they are willing to jump in and take the risk of becoming customers at all (and potentially put up with a new service’s ‘growing pains’), let alone how much they would be willing to pay for it. Then, 6) actually undertaking behavioural change (in this case, learning to use a new service, as well as potentially reorganising one’s daily life and changing one’s use of transport), which is a complex and challenging process that is all too easy to disrupt at any and all stages (as discussed in the section ‘Understanding users and what MaaS can offer’). Also, 7) users of transport rarely make unilateral decisions, but rather coordinate their activities with other household members, which affects transport needs and behaviours, i.e. if it were not difficult enough, the change process may entail a group of people changing their behaviours.”4

Since MaaS is touted as a way to impact travel behaviour, it is surprising that only very recently have researchers and practitioners recognised that behavioural science could be extremely useful in designing MaaS systems.

Issues with mobility data

Finally, there will be much more focus on addressing EDAI and ethical issues in mobility data generation, analysis, storage and use. This topic was discussed for the first time at ITS World Congress in 2021. Jennie Martin, Secretary General of ITS U.K., identified four major elements about ITS and mobility data that we need to consider, ensuring that it is not used in a negative way:

- Design: who is designing the systems that are generating, analysing and reporting the data?

- Data security: who has access to the data?

- Data location: where is it stored?

- Data equity: how long is the data stored and how is the data being used?

One very recent example of how these and more elements associated with mobility data will be addressed can be found in ‘Enabling the development of inclusive standards – Understanding the role of data and data analysis – Guide’5. This landmark document covers:

- The ways that data is selected, assessed and used in standards development, including different data types and processing

- Analysis of types of human bias

- How cognitive biases can change the way that data is interpreted and incorporated into decision-making processes

- How data and data models can introduce bias or exclusion into the standards development process

- The impacts of data bias or exclusion and the communities affected. This can include impacts related to protected characteristics, as well as non-protected characteristics6.

Furthermore, it builds the capability of standards makers to work with data with inclusion in mind, by helping them to develop their confidence and expertise. It also highlights the limitations of data and helps to minimise harm, as well as supports the production of more robust outputs that will serve a diverse population without bias. Overall, the documents strengthens the risk management of the organisations that develop standards7.

There will be much more focus on addressing EDAI and ethical issues in mobility data generation, analysis, storage and use.

References

- https://sparelabs.com/en/customer-stories/startran-paratransit/

- Ipek Sener, Texas Transportation Institute, who is Principal Investigator of this project

- https://itsworldcongress.com/the-congress-report/

- https://www.itf-oecd.org/sites/default/files/docs/maas-user-service-design.pdf

- https://shop.bsigroup.com/products/enabling-the-development-of-inclusive-standards-understanding-the-role-of-data-and-data-analysis-guide/standard

- https://shop.bsigroup.com/products/enabling-the-development-of-inclusive-standards-understanding-the-role-of-data-and-data-analysis-guide/standard

- Ibid

Carol Schweiger has over 40 years of experience, and is nationally and internationally recognised in transportation technology consulting. She has wide-ranging and in-depth expertise in several specialty areas, including technology strategies for public agencies, public transport technology, traveller information strategies and systems, and systems engineering. Schweiger has provided over 55 transportation agencies with technology technical assistance. She co-developed and was the lead instructor for five transit technology training courses for the National Transit Institute (NTI) and six modules regarding transit technology standards. She has also authored numerous Transit Cooperative Research Program (TCRP) Synthesis reports and full TCRP reports.

Related topics

Accessibility, Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS), Mobility Services, On-Demand Transport, Passenger Accessibility, Passenger Experience, Public Transport, Security & Crime

Related organisations

Citibus, Department for Transport (DfT), ITS United Kingdom, StarTran, Swedish National Road and Transport Research Institute, U.S. Transportation Research Board (TRB)

Related people

Carol Schweiger, Jana Sochor, Jennie Martin