Bus accessibility – more than just a ramp

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Posted: 1 September 2016 | Lesley Brown – journalist, Passion4Transport | No comments yet

In an article for Intelligent Transport, journalist Lesley Brown travels by bus on Line 96 in Paris to weigh up accessibility in the French capital…

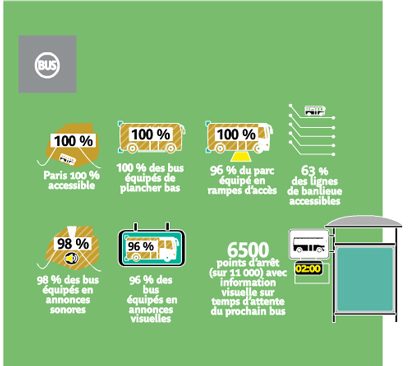

All the 63 bus routes serving inner Paris, operated by RATP, are deemed accessible for mobility impaired passengers. This means that 70% of all the stops along each line are adapted – level curb, uncluttered approach and departure pathways – to accommodate the retractable electric ramps on every bus. Yet there is more to accessibility than meets the eye…

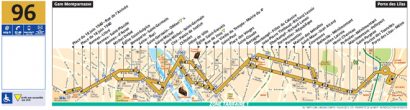

Passion4Transport took a ride on Line 96, running north-south through the capital between Porte des Lilas and Montparnasse station, together with Tony Rodwell, sales director of a U.K. ramp manufacturer, in order to observe just how easy it is to travel in La Ville Lumière as a wheelchair user.

On the road, in the streets

Line 96 has a total of 46 stops, of which just 2 are flagged wheelchair inaccessible. Yet at several along the route, even though no passengers made an ‘on-demand’ request (by pressing a button) to use the ramp, it clearly would have proved difficult to do so.

“The problematic of deploying the ramp at a stop, the ability, or not, of the bus to pull into the space by the pavement is what strikes me most,” commented Mr Rodwell during the ride. Indeed, street furniture such as litter bins, metal posts, and benches at times appeared too close for comfort, thus impeding easy access and swift flow of passengers through the double entry/exit doors located in the middle of the vehicle.

This observation raises the question as to whether RATP drivers receive special training on positioning the bus precisely to accommodate wheelchair boarding. “Yes they do,” responds RATP. “Our driver training centre integrates an ‘accessibility’ section that notably includes deploying ramps onto pavements.”

In response to our observation of pavement clutter, RATP said that together with the authorities in question (Ville de Paris for the inner city, communes for the suburbs), it makes sure that when street furniture (e.g. bus stops and litter bins) is replaced, the new equipment does not block bus entry and exits points at pavements.

“Ramp deployment may be further exacerbated by the density of traffic in Paris, the narrow streets, and attitudes to parking,” suggests Mr Rodwell. “It looks like cars and vans are parked more casually here than in London, for instance, without any concern about impeding the manoeuvring of buses.”

As a general rule, for inner Paris RATP depends on the Préfecture de Police to enforce regulations governing the access zones for bus stops. In the suburbs, however, the mayor of the commune [districts] in question and the local police are jointly responsible for ensuring this access is respected. “Furthermore, a certain number of our staff are officially allowed to issue parking fines if vehicles are blocking bus traffic,’ adds the operator.

Paris buses & accessibility – facts & figures / ©RATP – all rights reserved

Exploring specifications

A transport operator’s choice of ramp – electric (automatic) or manually operated – depends on criteria such as price, reliability, and maintenance, as well as stipulations by their governing authority. Clearly RATP has opted for electric, with each of the 4,500 buses making up its entire fleet now equipped.

During the trip on Line 96, the majority of buses seen were fitted with what Mr Rodwell described as an ‘underslung’ ramp, such as the one pictured above. He conceded that while there are a number of adverse features with this type of equipment, its installation is dictated by the space available.

Given the space constraints created by the chassis members and floor structure supports, to create the appropriate angle of entry, a section of the ‘bus floor’ must drop down to meet the ramp platform. This section should then rise up as it leaves the underfloor cassette where it is housed.

The mechanics needed to complete this operation are far more complicated than those of an integral floor ramp with its basic push out/pull back operation (see photo below). Hence a greater degree of maintenance is required and there is higher potential for malfunction in service – the risk being exacerbated by the retaining flap of the ramp being bottom hinged, potentially allowing for water run-off from the bus doors to enter the cassette.

Integral floor ramp on a Scania bus operating in Angers, France

Says RATP: “Although they occur very rarely, there are two types of problem-response scenarios for our automatic ramps: if the ramp malfunctions and is unable to deploy onto a pavement, the bus will continue its route then undergo repairs at the bus centre; if it deploys, either partly or fully, then remains blocked, then the bus itself is blocked. In this case our maintenance teams are called to the spot to intervene.”

A further potential downside of this underslung-type ramp is ground clearance, i.e. the distance between the road surface and ramp cassette. The less clearance, the greater the risk of damage to the cassette when travelling over road calming devices such as ‘sleeping policemen’. While not necessarily a major issue in Paris/France, this problematic is more of a concern in countries like Spain that tend to have more of these devices on their city roads.

In terms of the passenger experience, the transition from pavement to bus floor may also prove less smooth with this kind of ramp since there are a greater number of transitions for a wheelchair to traverse. There is also the potential for a trip hazard.

|

Accessibility concerns 12 million people in France: the mobility impaired, of course, but also older people, those that are sick, pregnant women, and travellers with heavy and bulky luggage. While the French Handicap Law of February 11, 2005* represented a significant step ahead, by stipulating all public buildings and transport (excluding metro systems) should be accessible for all by early 2015, in certain cases the compliance requirement has since been extended up to 2018. In 1995, Line 20 was the first in Paris to became wheelchair accessible; today, all the 63 within the capital are accessible. Out of the 277 suburban lines, 93 still need attention – a delay down to certain communes or their road managers charged with bringing the stops up to standard |

Stepping in the right direction

Since 2000, the European Union (EU) has implemented and developed several directives and regulations aiming at reducing barriers to public transport. Since then, the situation for buses overall in Europe has certainly improved; elsewhere in the world too.

“In my role as global sales & marketing director, I’ve witnessed the specification of buses improve markedly as cities across the world become more and more congested by an expanding car population,” confirms Mr Rodwell. “Countries such as India and Africa, where a bus body on a truck chassis with several steps to be climbed to gain entry are the norm, are now trending towards SLF [super low floor] or LF [low floor] vehicles fitted with ramps!

“Nevertheless, ramps on buses alone is unlikely to significantly increase ridership by mobility impaired people unless the bigger picture is also taken into consideration,” he warns.

Transport for all

Certainly, when it comes to providing adequate and mutually inclusive bus travel, ramps are part of a bigger picture. Related elements to be taken into account include travelling to and from stops, bus driver attitudes to picking up less able-bodied passengers, alternative modes of transport (dial-a-ride, mobility schemes), and rural routes lacking pavements onto which ramps can be deployed.

Bus travel ideally needs be a positive experience to entice people away from their cars. Introducing Wi-Fi, leather seats, and other bells and whistles may well suffice for able-bodied passengers. But surely the ultimate goal should be to enable everyone to board and alight easily so that they may share this positive experience too.

“Irrespective of the benefits to the operator, surely the service performance, i.e. ramp function and ease of access, should take precedence,” sums up Mr Rodwell.